When I was taught to cut rabbets in my first woodworking class, we made them with two cuts on the table saw. This technique is probably something you’ve seen in magazines and books. The work should be flat on the table for the first cut. For the second cut, you stand the work on edge and press it against the fence as you move the work over the blade. Your joint is now complete.

This technique has always been a problem for me. This technique never seems to make a perfect rabbet. The technique does have its strengths: Most woodworkers have a table saw and a rip blade to make the cut; when it works, it does produce a nice smooth joint. But after years of doing it this way, I concluded that this technique has several serious weaknesses:

- Standing on the edge of work requires a tall, rip fence, perfect balance and a zero clearance insert in your saw’s throat plate.

- It is time-consuming as it requires several test pieces and two saw sets to make the joint right.

- You have to move the saws guard out of the way for the second cut, no matter which brand of guard you have on your saw.

We decided to find a better way of making rabbets. Two good options were found. The first uses two scraps and a dado stack. The second is an improved two-step process thats virtually foolproof. Before we go on, let’s briefly explain why some methods aren’t as effective.

Rabbets by Hand Take Great SkillRabbets are one of the first joints woodworkers learn. Try building any sort of cabinet or shelf without it and youll know immediately how essential this simple open trench is.

The perfect rabbet should have square shoulders and a flat bottom. The cut should be straight and smooth. You shouldnt see marks from the tooling on the joint except on close inspection. You may have problems at assembly if any of these components are missing.

If the joints shoulders arent square, you likely are going to have an ugly gap between the rabbeted piece and its mate. Or worse, you will close the joint but the case will not be square. It will be more difficult to close the joint completely with clamps if the cut is uneven, rough, or has burn marks. Plus, a rough rabbet isnt going to be as good a glue joint as a smooth one.

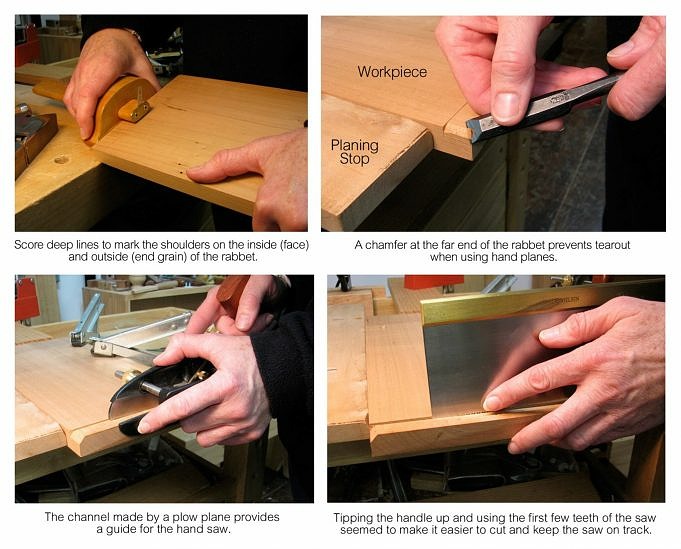

Woodworkers used hand tools to make rabbets before the advent of power tools. Ive done it this way, and it works great once you master a couple of skills. Before you can cut this joint with a rabbeting plane, you need to learn to tune the tool and sharpen the iron. For a beginner woodworker, this is not an easy task. Once you have a working tool, there are two important settings: the depth stop which limits the depth of the rabbet, and the fence which controls the width of the joints. Once you have these two settings, you can make passes until your tool stops cutting. Then your joint will be complete.

This technique is best for hand-tool enthusiasts. It does require some skill. Most woodworkers are going to opt for an electron-eating solution with an easier learning curve, such as with the router or table saw.

A table saw accessory fence lets you make perfect rabbets using one machine setup, almost always in one go.

Routers Available for All

I chose the router table as my first choice because it was extremely clean and maintains the squareness of joints shoulders.

After cutting many rabbets with my router table, it became clear that routers were not the best option for general casework rabbeting. Although it sounds absurd, here is what I found: Most routers are not powerful enough for the job. This means that you can only cut your projects in tiny, time-consuming pieces.

No matter what tools packaging or label claims, a router with 112 horsepower does not produce the same sustained torque as a contractor saw with 112 horsepower. Part of the problem is marketing hype among the router manufacturers, and part of the problem is in the way a universal router motor is built compared to a traditional induction motor on a contractor saw. Let’s just say that if you ask a router to cut a 310 cm wide x 320cm deep rabbet in one pass, it will either bog down or even stop.

A router is also noisier than a tablesaw, and large pieces of cabinet become difficult to maneuver on the router table. You could cut smaller rabbets on small pieces on the router table (drawers are about the right scale for most router tables). But heres how I feel about that: Learn the rabbeting process on one machine and then do it over and over the same way so you become an expert at that process. As you become more proficient at each technique, jumping from one technique to the next will slow down your progress.

To cut the joint, some people use their jointer with its rabbeting platform. The jointer is a powerful machine, and this technique actually works pretty well for narrow stock such as face frames and door parts. But try to rabbet the end of a 76 cm x 51 cm cabinet side and youll see why this isnt the way most people prefer to cut rabbets.

So I returned to the table saw which has guts galore, and a large table to try to find a new way to skin this wily creature.

Single Setup With Stack Dado Set

The finished rabbet’s depth is determined by the height of the dado stack. This measurement is 15 cm

The best thing about making a router table rabbet is the ability to do it with one tool. You can control the width and depth of the joint simultaneously, tweaking the height of the bit and the fence (which exposes the tooling) until the joint is just right.

To do this same thing on the table saw you need two things: a stack dado set and a long length of plywood you can clamp over the working surface of your rip fence. You can bury the dado stack inside the fence to make it work like a router table fence.

The accessory fence should be straight and at least 15cm thick. It should also be as long as the table saws fence. Because it is resistant to warping, plywood is an excellent choice.

The width is determined by the distance between the top of the left teeth and the fence. This measurement is 310 cm

When you first use the accessory fence, lower your dado stack to the table. Next, clamp the accessory fence to your rip fence and then position it so that about 120 cm of it covers the blades below. Next, turn on your saw and slowly lift the blades towards the fence until they are approximately 110 cm long.

Another necessity to ensure an accurate and safe cut is to use a featherboard that presses the work against the table. You can buy a variety of featherboards, or make your own. You can also see in the photo above that I added an aluminum T track (in a Rabbet) which allows me to adjust the featherboards position quickly. Thats mighty handy when dealing with project parts that are of different thicknesses.

Rabbeting follows the same rules as ripping and crosscutting. Use the fence to guide you when ripping grain.

Now you can start making rabbets. Use a 15 cm rule (see page 25 for almost-perfect 15 cm rulers), adjust the dado stack’s height to match the depth of your rabbet. Tip: Take some time to find the highest point of your blades teeth. When youve found that sweet spot, mark it on your table saws throat insert; I use a scratch awl. You can always use your ruler to measure the spot. Youll be amazed how much time this saves you.)

Next, use the saws to rip the fence so that enough dado stack is exposed to create the width of the rabbet. With practice, you can almost always hit that measurement exactly on the first try. Lock the height of the arbor on your saw. This is especially important if you own a benchtop or contractor saw. In smaller saws, the mere force of the cut can cause the arbor to creep downward. If it creeps just a bit, thats the worst. It is possible that you won’t discover the problem until after assembly.

Turn on the saw. Follow the same rules you do when ripping or crosscutting. You can press the work against the fence to rip it. Then push it through the blades. The same goes for work that is square or nearly square (such as the side of a base cabinet). Check the depth of the cut after your first pass. Use a ruler or dial calipers to check where the joint is at. Also, make sure that your featherboard is not lifting during the cut. If the joint is inconsistent, increase the tension on your featherboard or push the work a little harder against the saws table.

Sometimes taking a second pass will fix your problem. Even though it’s not the best solution, it is worth trying if you are stuck.

Remember: Any cup or warp in your workpiece can ruin the accuracy. Plywood isn’t always flat. If youre having trouble getting a consistent joint, check the work to see if its cupped or warped.

When crosscutting rabbets across the grain, you have two choices: Use a miter gauge if the stock is narrow or, for pieces wider than 20 cm, use the rip fence and a backing block behind the work. A backing block will stabilize the part during the cut. A backing block is not recommended for cutting narrow pieces as the work could slip into the cavity of the accessory fence. And thats when youll find out how tough the anti-kickback fingers on your featherboard are.

For crosscutting across the grain, use the miter gauge for narrow pieces or use the rip fence and a backing block (to prevent tear-out) for larger pieces.

To rabbet the ends of large case sides youll definitely have to forego the miter gauge. A backing block will help reduce the likelihood of tearing out grain as your work exits from the dado stack. A second pass can help ensure that your cuts are consistent, just like ripping.

As a bonus, you can cut rabbets this way with an overarm guard in place. We have removed the guard from these photos because it obscures the blades. However, it is an essential part of the setup.

This technique is not perfect, even though I love it. Crosscutting against the grain can make the cut a little rougher than if using a router. However, I haven’t had any glue problems when cutting joints with a dado stack. Cuts with the grain, on the other hand, are quite smooth.

Another cause for concern is your saws motor. Benchtop saws dont really have the guts to make casework rabbets (plus many dont have a mechanism to lock the height of the arbor a major problem). In fact, the fences of benchtop saws usually are too inaccurate to cut the joint using the two-step process mentioned earlier. A router table is a better option than a benchtop saw for cutting joints.

These joints are usually easy to pass for larger saws like cabinet- or contractor-style saws.

All things considered, I found that maneuvering workpieces on the larger table of the table saw is easier than cutting the same size pieces on the router table. Plus, the power of the table saw made the cuts easy to accomplish in one pass without taxing the machine or the tooling.

When making the cut in two stages, the first cut defines both the width and depth of your joint. Your work should be kept straight against the fence.

The Two-Step Process There is also a way to modify and simplify the table saw’s two-step process. This will make it easier for beginners or those who are not comfortable with the task of balancing pieces at the edge. A featherboard is the key. It is not easy to describe. It is also known as the motherboard in our shop.

The motherboard, shown in the photos below, needs to press the work against the rip fence right over the blade, so it looks a little different than the one used with the dado stack. This motherboard can only be used on the second pass.

The first pass defines the width and the depth of the rabbet. Use a saw blade with teeth that are flat on top, such as a ripping blade. Crosscut blades have teeth that cut the work like a knife and remove wood fibers. This will create V-shaped channels. You will have more problems with other blades such as triple-chip grinds. Stick with a rip knife.

Measure from the left or outside edge of the teeth to set the rip fencing. Once you have the desired width, adjust the rabbet. The fence should be locked. Next, use your 15 cm ruler to adjust the blade height until it is equal to the depth of the rail. Again, marking the highest projection of your saw blades teeth on your saws throat plate will save you hundreds of test cuts per year.

Make a test cut with the work flat on the saws table, as shown in the photo below left. If you like, you can use a featherboard to hold the work flat on the table, similar to the way I did it with the dado stack setup shown on page 10.

This featherboard is essential for rabbeting the table saw in just two steps. It holds the work stable and against the fence.

Once you have completed your first cut, get your saw set up to remove any remaining waste from the rabbet. The critical dimension is the distance between the fence and the blade. In essence, this distance is the amount of wood you want to remain on your piece when the joint is complete. Example: A rabbet measuring 110 cm in depth should be cut from a piece of wood that is 310 cm thick. For the second pass, make sure your fence is exactly 15 cm from the blade. Adjust the blade’s height until it removes all waste. The corner of the rabbet was already marked by the first cut.

It is important that the waste does not reach the blade’s edge. If the waste gets trapped between the blade and fence it will shoot back at you when it is cut. This could be less than ideal depending on where you are standing.

The other important point here is that you should either make or invest in a zero-clearance throat insert for your table saw. You want your pieces to be able to balance on the edge of the table for the second pass. This job is not possible with the stock throat insert included with most saws.

Your featherboard should be placed so that it presses against the fence, but not above the blade. The featherboard should allow the work through the blade, but it should also hold the fence in place. With the featherboard set, the cut is reasonably safe: The board will not tend to tip and the blade is buried safely in the work.

And the Winner is

During the second pass, everything is held in place by the motherboard. The result is a clean and accurate rabbet.

Ive cut hundreds of rabbets using both of these setups and I generally prefer using the dado stack method because it has one saw setup and the cut is made in a single pass.

It is also convenient to be able use the overarm guard while cutting, and to work flat on the table with all the parts. But if you dont have a dado stack (good ones start at about ), the two-step method is a sound alternative.

We wanted to discover which technique is preferred by beginning woodworkers. Sometimes, people new to the craft feel more intimidated than those who have been working for years. After a day of cutting rabbets both ways, the two beginning woodworkers in our workshop were able to make amazingly accurate rabbets using both techniques.

The only notable difference was that the dado-stack method required a little more upper body strength to keep the work to the table though the beginners were enamored with the simplicity of using just one pass. Two-step required more math, a little more finesse and more setup. My preference for math was not surprising as I avoid math whenever possible. WM

All 16 issues of Woodworking Magazine are available for download.

Recommendations for Product

These are the tools and supplies we use every day in our shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.